Comprehensive Macro Report: Geopolitics, The Risk In China, and The Carry Trade Unwind

How the structural regime is expressed in the positioning unwind we are seeing

The Monthly Macro Economic Report Is Below:

These reports break down how the macro regime is evolving and quantify all economic data points, directly connecting them to each asset class. They offer a comprehensive view of the economic landscape, linking data points to an informational edge across interest rates, FX, and risk assets. These reports provide a holistic picture of the macro regime and how to contextualize each asset within it.

If you are new to Capital Flows, you can watch the overview breaking down each aspect of the Substack and explaining how to use it:

Comprehensive Macro Report:

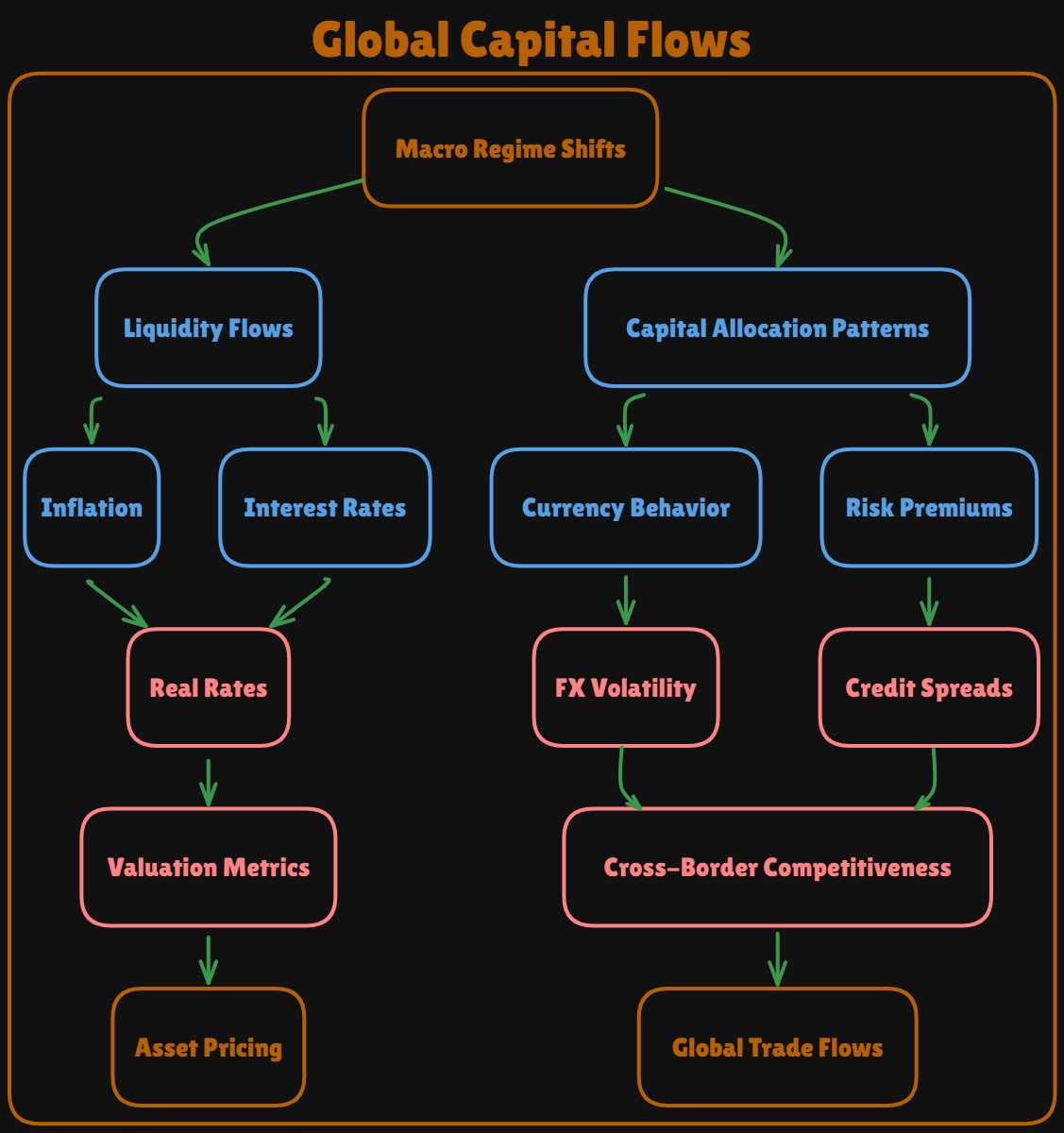

Over the past five years, the global macroeconomic landscape has been marked by profound structural shifts that extend well beyond typical business‐cycle fluctuations. On the financial front, different liquidity constraints, changing risk appetites, and different mechanics for how capital flows through markets. On the geopolitical side, the retreat from global integration has introduced new constraints on where and how capital can move, reshaping both currency regimes and the pricing of risk premiums.

Taken together, these dual regime changes signal that the next phase of macroeconomic policy‐making and market behavior will be more sensitive to inflation trajectories, interest rate differentials, and cross‐border flows than at any point in recent history. The interplay of shifting real rates, currency valuations, and credit conditions not only influences asset valuations—through adjustments to cash flows, price multiples, and risk premiums—but also underscores the heightened vulnerability of supply chains and trade relationships in an era of rising geopolitical frictions.

An older report by Totem macro perfectly encapsulates these ideas and visualizes it (Whitney explains these ideas better than anyone!):

The following diagram (inspired by Totem Macro) illustrates the core logic: two overlapping regime changes (“Financial” and “Geopolitical”) usher in constraints on both the overall abundance of liquidity and its geographic or geopolitical direction, thereby shaping inflation, rates, currency regimes, and risk premiums. In turn, these factors drive core outcomes such as valuation multiples, cash flow forecasts, foreign exchange dynamics, and asset volatility.

Over the past several years, the global economy has experienced macroeconomic transitions that carry significant implications for investment strategies, corporate planning, and policy frameworks. These shifts encompass both long-term structural realignments—such as demographic changes and capital migrations—as well as cyclical patterns in credit, demand, and inflation. By examining these layers methodically, we can gain a nuanced understanding of how liquidity conditions, capital flows, and regulatory shifts shape market outcomes. By systematically examining each structural, cyclical, and short-term dimension, this report explains how they interconnect to form a cohesive macroeconomic framework. In turn, it equips investors with a quantifiable framework for decision-making in both asset markets and the real economy.

Macro Report Index Overview:

Structural Macro Shifts

Demographic and Technological Drivers

Regulatory and Policy Transformations

Capital Distribution and Evolving Market Structures

Economic Structure

Growth, Inflation, Liquidity, Credit

International Connections: Balance of Payments, Exchange Rate Dynamics, and Global Capital Flows

Short-Term Economic Signals

Data Releases and Scenario Analysis

Market Positioning

Correlations and Momentum

Conclusions and Strategic Implications

Integrating Structural, Cyclical, and Short-Term Perspectives

Forward-Looking Scenarios and Contingency Plans

Strategy Synthesis and Tactical Implementation

Structural Macro Shifts

Demographic and geographic foundations shape the macroeconomic trajectories of both nations and regions. In the case of the world’s two largest economies, the United States still experiences population growth—albeit at a decelerating pace—while China, facing a declining birth rate and an aging population, has already begun to shrink. This divergence informs not only domestic labor markets and long‐term consumption trends but also the broader global distribution of economic power. The following chart illustrates these contrasting population trajectories:

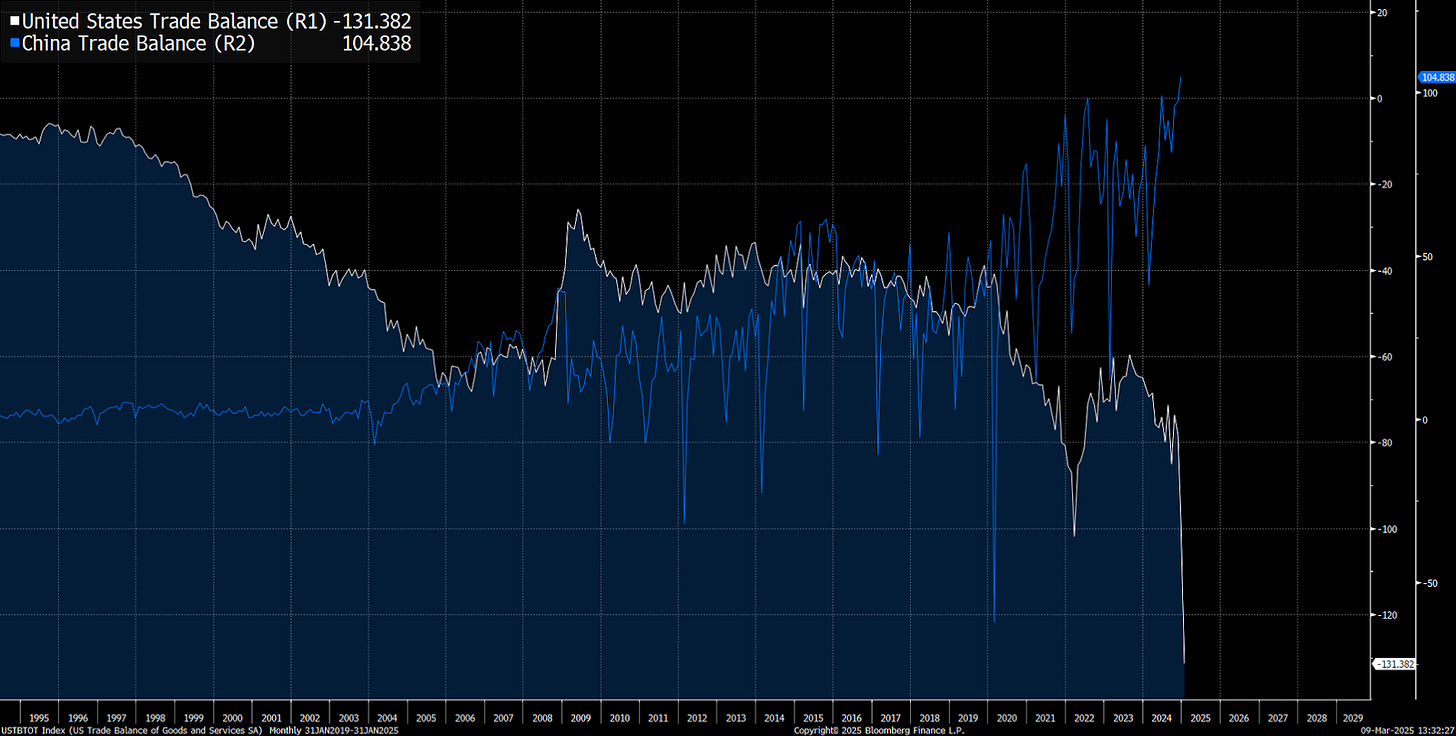

As Trade Wars Are Class Wars by Matthew C. Klein and Michael Pettis explains, demographic forces and the dollar’s reserve currency status interact in a reflexive feedback loop that shapes global trade imbalances. Slowing population growth and aging in China encourage higher household savings, fueling its exports and current account surplus; in contrast, the United States—still supported by more robust demographic trends—can rely on sustained consumer demand that contributes to its trade deficit. At the same time, global confidence in the dollar as the principal reserve asset allows the United States to finance these deficits on favorable terms, reinforcing consumption and investment even when savings are comparatively lower. This privileged monetary position, in turn, helps perpetuate demographic advantages such as immigration‐driven labor force growth, which further supports consumer spending and draws in additional capital. In this way, an aging, high‐saving China and a more demographically dynamic, deficit‐running United States become interlocked partners in a system where currency supremacy and demographic trends feed into each other, perpetuating the underlying imbalances.

This connection between demographics and trade has been covered extensively in academic literature:

International Monetary Fund (2021). “Demographic Pressures, External Balances, and the Dollar: Revisiting US-China Trade Dynamics.”

Quote: “Population aging in China appears to raise household savings, sustaining China’s current account surplus, whereas continued demographic expansion in the United States underpins its deficit position.”

National Bureau of Economic Research (2019). “Changing Demographics and Global Imbalances: A US-China Perspective.”

Quote: “Our findings suggest that declining birth rates in China, alongside sustained immigration in the United States, have contributed to trade imbalances by altering relative consumption propensities and asset demand.”

Peterson Institute for International Economics (2022). “Reserve Currencies, Demographics, and Persistent Trade Gaps.”

Quote: “With the US dollar continuing as the principal reserve asset, external deficit financing has proven less burdensome for the United States than for economies whose currencies lack global reserve status.”

This demographic and trade structure between the US and China frames their geopolitical tensions. We continue to see China employ subversive attacks through multiple political, trade, or financial avenues.

Geopolitical Attacks:

China’s AI Ambitions and “Leakage” of Restricted NVDA Chips

Despite official U.S. bans on the sale of Nvidia’s most advanced AI chips to Chinese entities, investigations by multiple outlets suggest these GPUs are still reaching China through intermediaries. Recent Bloomberg reports indicate third‐party distributors operating out of Southeast Asia and Mexico continue to re‐export chipsets nearly identical to Nvidia’s A100 and H100 models. Similar findings from The Wall Street Journal and analyses by CSIS reveal sudden spikes in semiconductor orders from allegedly neutral regions, heavily resembling restricted U.S. hardware specifications.

Bloomberg (2023). How Nvidia’s AI Chips Are Still Flowing to China

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-08-21/how-nvidia-s-ai-chips-are-still-sold-to-chinaThe Wall Street Journal (2023). How Chinese Tech Giants Are Getting AI Chips Despite US Ban

https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-chinese-tech-giants-are-getting-ai-chips-despite-us-ban-8a80f33fCSIS (2022). Semiconductors and Security Brief

https://www.csis.org/analysis/semiconductors-and-security-brief

Exporting By Proxy: China’s “Offshoring” of Goods Through Mexico and Others

Next, China’s “proxy exports” exploit partners like Mexico to bypass tariffs. Policy briefs from Chatham House and the Carnegie Endowment reveal large upticks in high‐tech shipments from Mexico to the U.S. that seem to originate from Chinese supply chains. By re‐labeling partial assemblies as “made in Mexico,” Chinese producers navigate around higher U.S. tariff brackets and tighter country‐of‐origin rules.

Chatham House (2023). Global Value Chains and Proxy Export Tactics

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/06/global-value-chains-and-proxy-export-tacticsCarnegie Endowment for International Peace (2022). Trade Diversion and Rules of Origin Loopholes

https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/11/01/trade-diversion-and-rules-of-origin-loopholes

Although punitive tariffs and export bans began under the Trump administration, many remain firmly in place as of 2023, widening to include top‐tier AI hardware. Attempts to choke off China’s semiconductor pipeline reflect a broader recognition of AI’s strategic value. Yet the release of DeepSeek underscores the challenge of restricting high‐tech progress: advanced models can rapidly diffuse knowledge and algorithms beyond hardware constraints. Commentaries in Foreign Affairs and RAND show how nations are pivoting from classical industrial expansions to an AI‐centric race.

Foreign Affairs (2022). The Post-Industrial Race for AI Supremacy

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2022-09-21/post-industrial-race-ai-supremacyRAND Corporation (2023). Tariffs, AI, and the Evolving Geopolitical Chessboard

https://www.rand.org/pubs/white_papers/WP2023-001.htmlBrookings (2023). DeepSeek, the Next Frontier in Machine Learning

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/deepseek-the-next-frontier-in-machine-learning

The US–China Axis: Linking Balance of Payments, the Impossible Trinity, and Global Markets

Increasingly, the global trading system, financial flows, and geopolitical alignments are shaped by two central players: the United States and China. Their economic heft, unique financial architectures, and divergent policy priorities create a framework within which virtually all other economies operate. Key to this dynamic are (1) the Chinese balance of payments and Beijing’s approach to the “impossible trinity,” and (2) the dollar’s reserve‐currency role, which grants the United States a different rendition of the same trilemma.

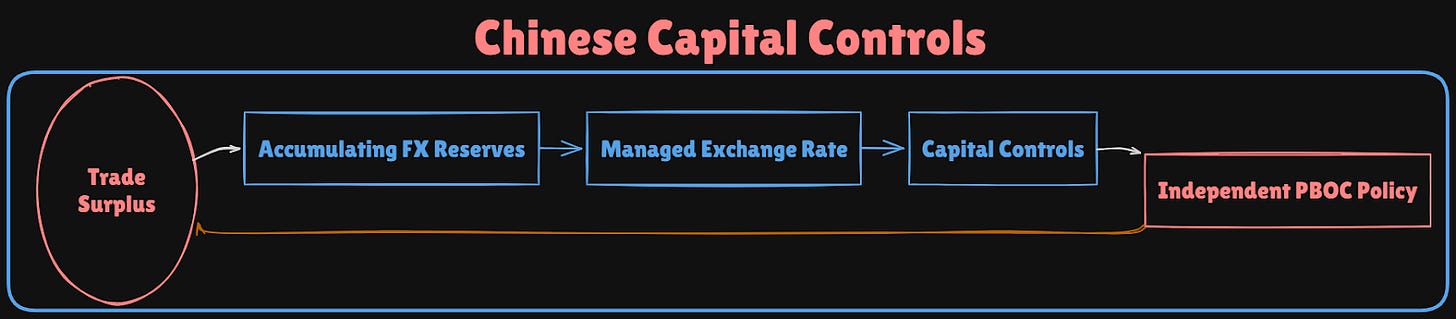

China’s Balance of Payments and Its Impossible Trinity:

China largely maintains capital controls, a managed exchange rate, and partial monetary independence—something classical theory deems impossible to do simultaneously. By restricting capital flows, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) smooths renminbi (RMB) fluctuations and accumulates or offloads reserves. This plays out directly in China’s balance of payments, where persistent trade surpluses, controlled currency adjustments, and regulated outflows shape both domestic credit conditions and global markets.

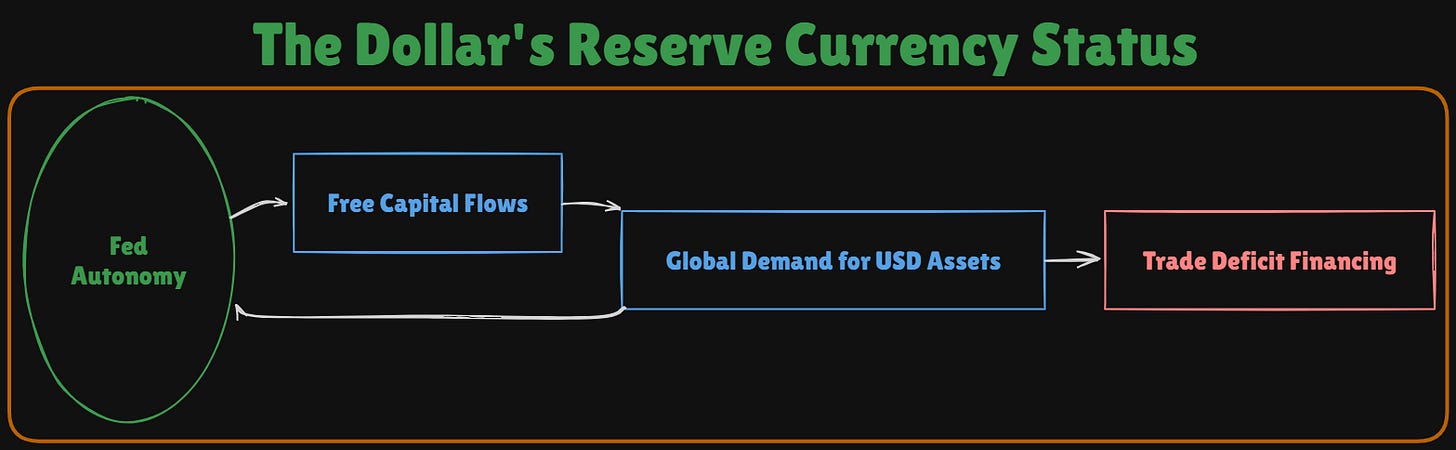

The Dollar’s Reserve‐Currency Status and the US “Trilemma”

The United States opts for free capital movement, a floating exchange rate, and an autonomous Federal Reserve. Yet because the dollar is the world’s primary reserve currency, the Fed’s decisions ripple through global liquidity. This effectively morphs the traditional trilemma: external actors anchor themselves to USD assets (Treasuries, corporate bonds), allowing the U.S. to finance deficits more flexibly.

Recent Trump‐Era and 2023 Policy Shifts: Tariffs, Exchange Differentials, and Equity Market Divergence

Tariffs on Chinese imports, begun under President Trump, have largely persisted in some form, reflecting Washington’s broader tech containment strategy. On the Chinese side, the PBOC’s interventions balance domestic policy needs against global market pressures. Rate differentials between the Fed and PBOC can drive equity market cycles—U.S. equities often see robust foreign inflows chasing the “global risk‐free” currency, while Chinese equities rely more on internal liquidity changes subject to capital controls.

Tangible Differences Between the Two Economies: Spillover in Growth, Inflation, and Liquidity

U.S. growth remains consumption‐driven and buttressed by global demand for the dollar, while China’s high savings rate and export‐led approach lean on capital controls and managed currency policies. Fed tightening or loosening quickly resonates worldwide, whereas PBOC credit cycles more directly affect commodities and EM exporters. The net effect is a two‐pole environment—nations either orbit the U.S. for financial stability or look to China for trade expansion.

Putting It All Together

The interplay of Chinese capital controls, export surpluses, and the US dollar’s reserve‐currency privilege define much of the current global macro backdrop. By combining trade policy changes—especially those initiated during the Trump era—with interest‐rate differentials, each economy exercises a gravitational pull on growth, inflation, and liquidity worldwide. In effect, the US–China tug‐of‐war forces other nations to balance around them, shaping everything from commodity cycles in emerging markets to exchange‐rate regimes in developed economies.

It is within this context that the following variables can be interpreted accurately:

Currency regime differentials

Trade balance differentials

Growth differentials

Inflation differentials

Short end rate differentials

Long end rate differentials

Currency Regimes:

Below is a breakdown of every major country and the respective currency regime to show the spectrum across the impossible trinity:

G10

United States (USD)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: US opts for open capital flows and monetary autonomy, so it cannot fix the exchange rate.

USD’s reserve‐currency role provides unique flexibility to finance deficits easily; Fed decisions shape global liquidity.

Canada (CAD)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Open capital flows + floating FX → BoC retains independent policy.

Typically aligns policy with Fed but no formal peg.

Japan (JPY)

Currency Regime: Free Float (with strong interventions in bond markets)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Theoretically open capital flows + floating FX, but BoJ manages bond yields (yield curve control).

Occasional FX interventions reflect trade‐off: preserve monetary independence at the cost of letting FX fluctuate.

United Kingdom (GBP)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: BoE maintains monetary autonomy; open capital account with no fixed rate.

High inflation episodes can pressure GBP, but it remains free‐floating.

Switzerland (CHF)

Currency Regime: Free Float (actively intervenes to curb CHF strength)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Strong capital inflows force SNB interventions to prevent excessive CHF appreciation.

Open capital flows + near‐independent policy, but not a rigid peg/fix.

Sweden (SEK)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Riksbank sets independent policy; capital flows fully open; SEK not fixed.

Only minimal interventions to reduce extreme volatility.

Norway (NOK)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Norges Bank has monetary autonomy and open capital flows, leaving NOK to float.

Oil revenues sterilized via the sovereign wealth fund.

Australia (AUD)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: RBA inflation targeting with open capital flows, floating exchange rate.

Minimal direct FX intervention unless extreme volatility.

New Zealand (NZD)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Fully open capital flows and free‐floating NZD → RBNZ retains monetary autonomy.

Interventions are rare, generally letting the market determine NZD.

Euro Area (EUR) (Germany, France, Italy, etc.)

Currency Regime: Free Float (Single Currency)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Single currency among multiple nations → each surrenders independent monetary policy to the ECB, but keeps open capital flows.

Euro is freely floating overall; no individual country can fix its own rate.

EMEA

Russia (RUB)

Currency Regime: Floating (managed)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Official float but subject to capital controls (especially post‐sanctions).

By restricting capital mobility, Russia can maintain partial currency stability and some monetary autonomy.

Turkey (TRY)

Currency Regime: De Facto Managed Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Turkey attempts some monetary autonomy, but uses sporadic capital controls and interventions.

Exchange rate is not firmly fixed; managed when volatility spikes.

South Africa (ZAR)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: SARB pursues independent policy with open capital flows, so ZAR must float.

Volatile amid global risk‐on/risk‐off sentiment.

Nigeria (NGN)

Currency Regime: Multiple Rates / Managed Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: FX controls and parallel markets reduce capital mobility.

Allows some monetary independence, but official vs. parallel rates cause distortions.

Egypt (EGP)

Currency Regime: Managed Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Moves between partial devaluations and capital controls to preserve policy autonomy.

Reliant on external financing, shaping the FX regime.

Asia (Non‐G10)

China (CNY/CNH)

Currency Regime: Managed Float + Capital Controls

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: By restricting capital flows, PBOC can manage the RMB’s exchange rate and retain a fair degree of monetary autonomy.

Offshore CNH is more market‐driven, but still guided by daily fix/interventions.

India (INR)

Currency Regime: Managed Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: RBI intervenes to stabilize INR; partial capital controls exist.

Preserves mostly open capital account but steps in to moderate volatility.

Indonesia (IDR)

Currency Regime: Free Float (with interventions)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: BI tries to stabilize IDR without a formal peg.

Open capital flows → partial sacrifice of fixed exchange rate; policy remains largely independent.

Malaysia (MYR)

Currency Regime: Managed Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: BNM intervenes intermittently; mostly open capital account but some selective controls historically.

Previously pegged during the 1998–2005 crisis period.

Thailand (THB)

Currency Regime: Managed Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: BoT intervenes to smooth volatility; mostly open capital flows.

No strict peg, preserving partial monetary independence.

South Korea (KRW)

Currency Regime: Managed Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: BoK intervenes if KRW swings excessively; capital flows largely open.

Full monetary autonomy is somewhat constrained by external factors and capital mobility.

Singapore (SGD)

Currency Regime: Managed Float w/ NEER Basket

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: MAS uses the exchange rate (NEER band) as its main policy tool, rather than a policy rate.

Capital is mostly free; monetary autonomy comes from controlling currency within a band.

Latin America

Brazil (BRL)

Currency Regime: Free Float (occasional interventions)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: BCB aims for monetary autonomy and open capital flows, so BRL must float.

Uses swaps or direct USD sales to manage short‐term volatility.

Mexico (MXN)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Banxico inflation targets with open capital flows → flexible MXN.

Intervention only under severe volatility.

Argentina (ARS)

Currency Regime: Multiple Rates / Capital Controls

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Restricting capital flows allows partial monetary policy independence and semi‐managed FX.

Frequent devaluations under high inflation.

Chile (CLP)

Currency Regime: Free Float (some interventions)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Open capital flows + monetary independence → CLP floats.

Central bank intervenes only to smooth large swings.

Colombia (COP)

Currency Regime: Free Float

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: With open capital flows and inflation targeting, COP must float.

Occasional interventions are minimal.

Middle East

Saudi Arabia (SAR)

Currency Regime: Peg to USD

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Fixed FX + open capital flows → forfeits monetary autonomy.

Rates track the Fed to maintain the peg.

UAE (AED)

Currency Regime: Peg to USD

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Similar logic as Saudi; open capital flows + USD peg leaves monetary policy tied to Fed decisions.

Qatar (QAR)

Currency Regime: Peg to USD

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Peg + open capital flows → QCB has little independent policy.

Must follow Fed to sustain the peg.

Kuwait (KWD)

Currency Regime: Peg to a Basket (USD‐heavy)

Key Notes:

Impossible Trinity: Heavily USD‐weighted peg with open capital flows → limited monetary independence.

Must align with Fed stance to keep the basket stable.

While we are not going to cover every country noted above, it is important to understand that capital flows function in the international arena of various currency regimes. It is within these regimes that cross-border flows operate.

Economic Regime:

The structural components noted above frame the changes in global growth, inflation, liquidity, and credit dynamics. As greater integration and global trade have taken place over the past 40 years, inflation has moved in a tighter and tighter relationship. The inflationary impulse we saw over the last 4 years was global in nature, with all major central banks following the Fed in rate hikes.

We can see that short-end rates across all major economies moved in perfect coordination following the Fed. Why is this? Because these countries need to maintain a proper stance relative to the Fed and the dollar. However, interest rates in China have diverged considerably from the rest of the world.

The primary reason for this divergence of Chinese rates from global rates is a prolonged deleveraging in their real estate sector. The chart below shows how the Goldman Sachs Real Estate Index for China has been leading the downside for broad Chinese equities and interest rates.

The underlying sector returns of the Hang Seng and CSI300 show that the primary source of the recent rally is almost completely from Chinese tech.

It is very clear in the rotation that capital is being pulled away from the AI theme in the US and shifting to the AI theme in China. This rotation obviously has significance surrounding DeepSeek, but it goes beyond this to the geopolitical dynamics taking place under the surface.

Bessent is the most market-aware Treasury Secretary in US history and is watching the dynamics unfold with China very closely (link). This is one of the reasons the tariffs carry a heightened significance. It is very possible that Trump and Bessent put greater amount of tariff pressure on China and increase the intensity of threats as the rotation from US technology to Chinese technology intensifies.

This short piece by the Washington post illustrates this geopolitical tension between the US and China right now. It is clear that any flow of goods, services or capital between the two countries is in no way neutral.

"Chinese Tariffs Set to Hit U.S. Farm Products as Trade Tensions Mount

By Christian Shepherd and Lily Kuo

(Washington Post) -- BEIJING — Chinese tariffs on a wide array of U.S. agricultural products were set to take effect Monday as Beijing remains defiant in the face of U.S. pressure — at the same time as urging Washington to come to the negotiating table.

China's retaliation, its response to President Donald Trump's decision to raise tariffs on all Chinese goods to at least 20 percent, is the latest escalation in a brewing trade battle between the world's two largest economies.

Beijing last week said it would impose tariffs of up to 15 percent on a raft of U.S. farm products from March 10, targeting some of the United States' most important exports to China.

China is the largest market for American farm products, last year importing almost $20 billion in soybeans, corn, cotton and the other U.S. farm products that will be subject to the new tariffs, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The measures were in retaliation for Trump's decision earlier this month to increase tariffs on Chinese products by another 10 percent, on top of the 10 percent imposed last month, bringing the total duty on some Chinese products to 45 percent. Beijing also placed export controls and trade restrictions on more than 20 U.S. companies.

Trump has also been threatening to impose tariffs on Canada and Mexico, but last week postponed his plans for another month after talks with the leaders of those countries.

Although top Trump administration officials, including Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, have had calls with their Chinese counterparts, the president has had no such conversation with his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping.

China's leaders have instead remained defiant in the face of ever higher tariffs, despite a slowing economy and falling prices.

In addition to weak spending and high unemployment, China is experiencing stubborn deflation. Data on Sunday showed consumer prices dropped further in February, falling 0.7 percent from a year earlier.

But China has relatively few cards to play given that it runs an enormous trade surplus — approaching $300 billion last year — with the United States.

Beijing has instead retaliated with a variety of novel measures. The retaliatory package by Chinese authorities last week included moves to restrict imports of gene sequencing technology from American biotech company Illumina and an investigation into whether an American fiber optics company was skirting Beijing's earlier anti-dumping measures.

China has, however, also signaled it is open to negotiations with the Trump administration. On the same day as hitting back against tariffs, Chinese authorities released a white paper claiming that its law enforcement agencies were cracking down on the production and shipment of fentanyl-related substances.

China's top diplomat, Wang Yi, on Friday illustrated this carrot-and-stick approach, striking a defiant tone while also calling on Trump to reconsider the trade war.

'No country can fantasize that it can suppress and contain China while developing good relations with China,' Wang said at a news conference in Beijing.

'China and the United States have extensive common interests and broad space for cooperation. They can become partners, achieve mutual success and prosper together,' he added.

On top of this, we are seeing deflation in the Chinese data, indicating underlying issues and risks in the economy.

The PBOC frequently intervenes around the 7.0 mark for USD/CNH, particularly when domestic growth slows, and it injects liquidity to stabilize the economy. These liquidity infusions can weaken the exchange rate, so the PBOC draws on its current account surplus—held in foreign reserves—to prevent excessive depreciation and limit capital flight. The sell-offs in equities, coupled with moves down in interest rates, overlap with the short-term tops around the 7.0 mark in USD/CNH. The stronger the position that China establishes in tech, the less pressure they have to manage its exchange rate on a marginal basis.

While financial and economic actions might seem cordial, both the US and China are attacking each other and trying to exploit the other’s weaknesses through policy tools for goods, services, liquidity, and credit. This is WHY the tariffs are so significant right now. They can put considerable pressure on the Chinese economy. The reason this is creating uncertainty in the global economy is because China is the largest exporting country in the world and global value chains remain a fundamental structure for everything.

As tariffs interact with the specific interest rate environment we are in, short-end rate differentials and carry trades begin to carry outsized significance for asset prices. We are seeing 2 year rates for Canada and Mexico diverge due to the changes in underlying growth and tariff risks.

The G10 carry trade index is falling in a similar pattern to August 2024 (see this paper: Link). However, we are seeing shifts in currencies with traders putting up exposure in China, Europe, and other Latin American countries.

The geopolitical context is creating a regime where capital is shifting and carry trades are unwinding. However, instead of it being an outright liquidation, we are seeing a rotation of capital internationally. This is taking place as growth and inflation across major countries remains relatively stable. We are not seeing signs of another inflationary spike or the beginning of a recession. However, the way in which positioning is unwinding along with how its interacting with tariffs in the geopolitical context, is likely to set the stage for the next move in growth and inflation.

In summary, although global growth remains relatively steady, significant geopolitical developments are unfolding that affect capital movements. While delinquencies and credit spreads have not shown a persistent rise across major economies, unwinding carry trades are driving international rotations of capital. With these factors in mind, we can now examine the latest data releases and signals across countries to understand their impact on interest rates, FX, and risk assets.

Short‐Term Economic Signals

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Capital Flows to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.