Credit Cycle Playbook: Redundency Planning

The driver of reflexivity in macro cycles

Redundancy Planning:

One of the fundamental things that doesn’t bode well in the media industry is redundancy planning and preparation. If I go onto a news program and tell them that I simply have redundancy plans for every scenario and I’m waiting for the signals to trigger, it’s not an exciting perma bear or perma bull narrative. However, it is this TYPE of thinking that practitioners use to operate in financial markets.

We are going to be digging into one of THE most critical aspects of macro, the credit cycle. I recently published a Twitter thread on this (link), but I want to expand on this and build more of a redundancy plan around it. The worst thing that could happen is that you are ill-equipped for a melt-up, melt-down, or any type of market in between. Everyone knows the challenge of having a view about an extreme market impulse only to get chopped up for weeks or months. So we are going to cover the playbook for credit today.

A Proper Definition Of Credit:

Credit imposes a non-negotiable countdown on every balance sheet from the moment funds are drawn. I am going to break this down into 3 parts:

First, tracing how borrowing drags future purchasing power into the present and fixes a hard maturity date that cannot be wished away.

Second, showing why crises erupt from the mismatch between short-dated liabilities and long-dated assets, not merely from headline debt levels.

Third, focusing on the national accounts, where one firm’s interest expense is another’s income—until synchronized optimism stretches the system and aggregate cash flow can’t cover the bill.

This section isn’t about predicting a doom-loop or a perpetual melt-up; it’s about wiring redundancy triggers in advance so the next liquidity squeeze becomes an execution checklist, not a surprise.

1. Credit is a deliberate time-shift of purchasing power.

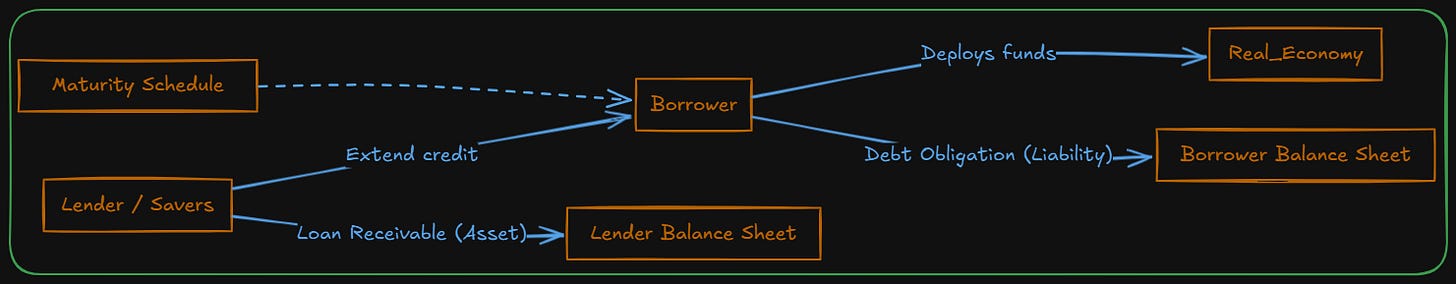

Credit transforms current surplus savings into future cash-flow claims: the lender books a receivable (asset) while the borrower records a payable (liability). Because repayment is locked to a specific maturity schedule, credit instantly embeds a temporal constraint on the real economy—capital deployed today must generate cash flows tomorrow sufficient to service both principal and interest. In competitive markets, this constraint disciplines firms and nations alike: those that deploy borrowed funds into projects with sub-par risk-adjusted returns will see funding costs rise, eroding margin and market share.

2. Deleveraging is triggered by an asset-liability duration mismatch, not by gross issuance alone.

When the life of a borrowed dollar (short-dated liability) is shorter than the cash-flow horizon of the asset it finances, roll-over risk surfaces. A shock to funding costs, collateral values, or operating income forces borrowers to liquidate assets or cut investment prematurely—igniting the classic deleveraging spiral. The problem is structural: a balance-sheet engineered on thin equity and aggressive short-term leverage becomes hypersensitive to volatility spikes, margin calls, and policy tightening, irrespective of how “low” aggregate credit growth might appear ex-post.

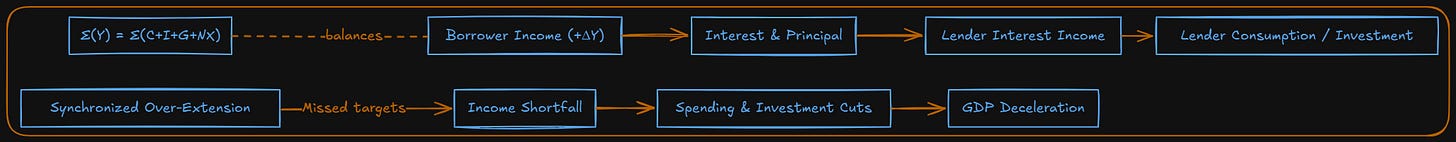

3. In macro‐accounting, one agent’s interest expense is another’s interest income, so credit expansion merely reshuffles cash-flow timing—until mismatches accumulate.

National accounts net to zero: every dollar borrowed to accelerate consumption or capex today appears elsewhere as income to a lender, contractor, or supplier. The danger lies in synchronized over-extension—if many balance sheets rely on the same optimistic growth assumptions, the collective income needed for debt service may fail to materialize, producing a negative feedback loop that compresses spending, profits, and ultimately GDP. Thus credit is the hinge between micro balance-sheet choices and the macro identity C + I + G + NX = Y, dictating whether growth is self-reinforcing or self-limiting.

Banks, The Fed, and Credit:

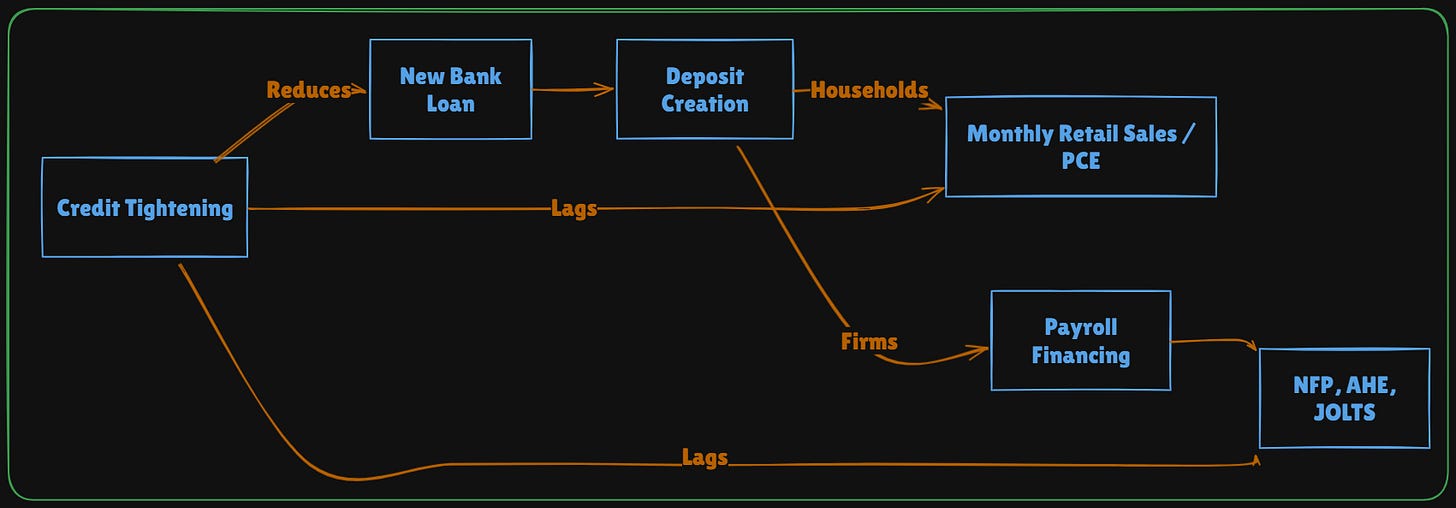

1. Credit flows show up in monthly consumption and labor-market prints almost immediately.

When commercial banks expand balance sheets, new loans create matching deposits that households and firms can spend. Those deposits fund retail sales, PCE, and inventory builds, which appear in Census and BEA data within one-to-two reporting lags. Firms that draw on revolving credit to finance working capital simultaneously expand payrolls, lifting NFP, average hourly earnings, and JOLTS openings. Conversely, tighter credit lines or higher debt-service burdens force cutbacks that filter into these same high-frequency indicators. In short, the banking system’s credit pulse is the leading edge of both consumption and labor data

2. Fractional-reserve banks manufacture broad money; the Fed’s reserves only enable interbank settlement.

A commercial bank funds each dollar of new lending with a fraction of central-bank reserves and capital; the rest is a self-created deposit liability. That process—asset creation matched by liability creation inside the private sector—is fundamentally different from the Federal Reserve’s open-market operations, which merely swap Treasuries for reserves between the Fed and primary dealers. Reserves stay trapped in the banking system’s plumbing, settling payments and meeting liquidity regs, but they do not finance end-user spending unless a bank chooses to convert reserve capacity into new credit risk.

See Conks on this topic:

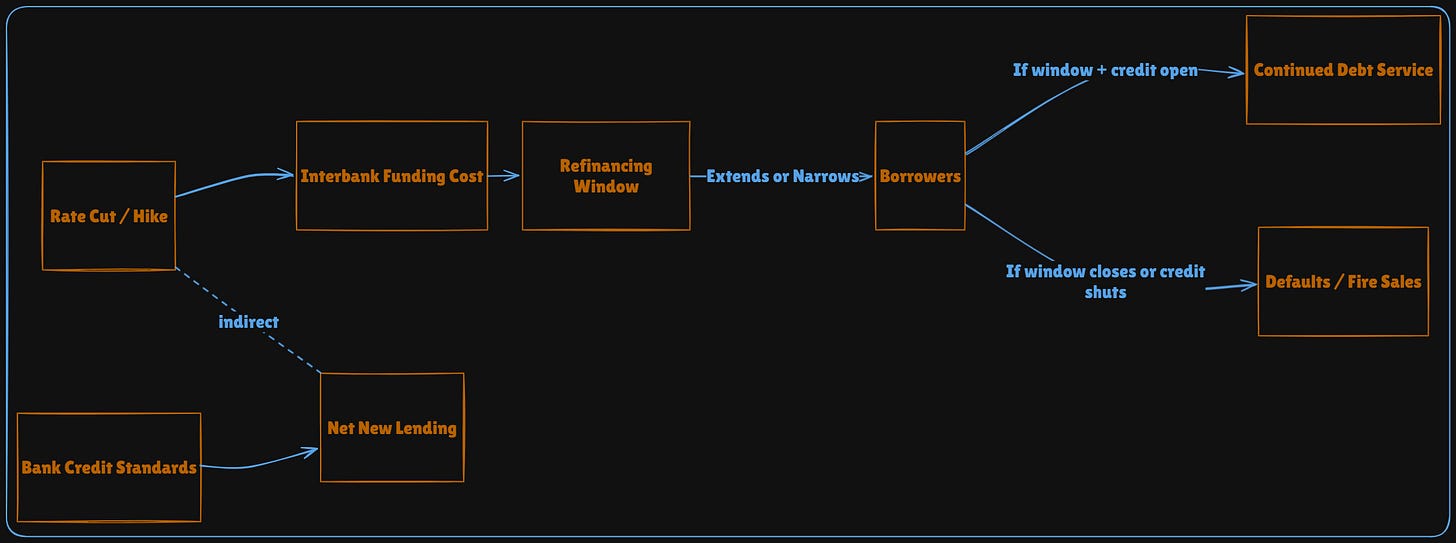

3. Policy rates move the liquidity clock, but defaults hinge on maturity structure and credit risk priced by banks.

When the Fed cuts, term funding costs fall and liquidity rises, extending the refinancing runway for borrowers whose debts roll in the next 3–12 months; hikes do the opposite. Yet nothing forces banks to originate new loans: credit creation still depends on expected loss-given-default, borrower cash-flow coverage, and collateral values. Defaults or “melt-ups” therefore occur only when the temporal window (maturities coming due) collides with a sudden reassessment of credit risk, not simply with a policy tweak. This dual dependence explains why aggressive hiking cycles can coexist with low default rates—until a maturity wall approaches—or why aggressive cuts sometimes fail to ignite credit booms when banks perceive deteriorating fundamentals.

Credit Cycle Backtest:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Capital Flows to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.